For twelve seasons Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts has presented a film series fittingly titled “Movies Houstonians Love.” Beginning in 2005 with the cult hit Barbarella the series has seen Houston leaders from all walks of life show their love of cinema by selecting one of their favorite films.

Past presenters have included Oscar-nominated filmmaker Richard Linklater (with Season 2’s Some Came Running), University of Houston president Renu Khator (Mr. and Mrs. Iyer), current Vice Mayor Pro-Tem Ellen Cohen (Mr. Smith Goes to Washington), and author and former poet laureate Gwendolyn Zepeda (Hedwig and the Angry Inch).

Even Houston’s elected mayors have participated in Movies Houstonians Love. Bill White was part of the inaugural season with his selection of Peter Bogdanovich’s The Last Picture Show. Three years later Bob Lanier picked For Whom the Bell Tolls, starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman. Annise Parker, who was Houston’s second female mayor and one of the first openly gay mayors of a major U.S. city, had area residents clicking their heels together and repeating “there’s no place like home” with The Wizard of Oz.

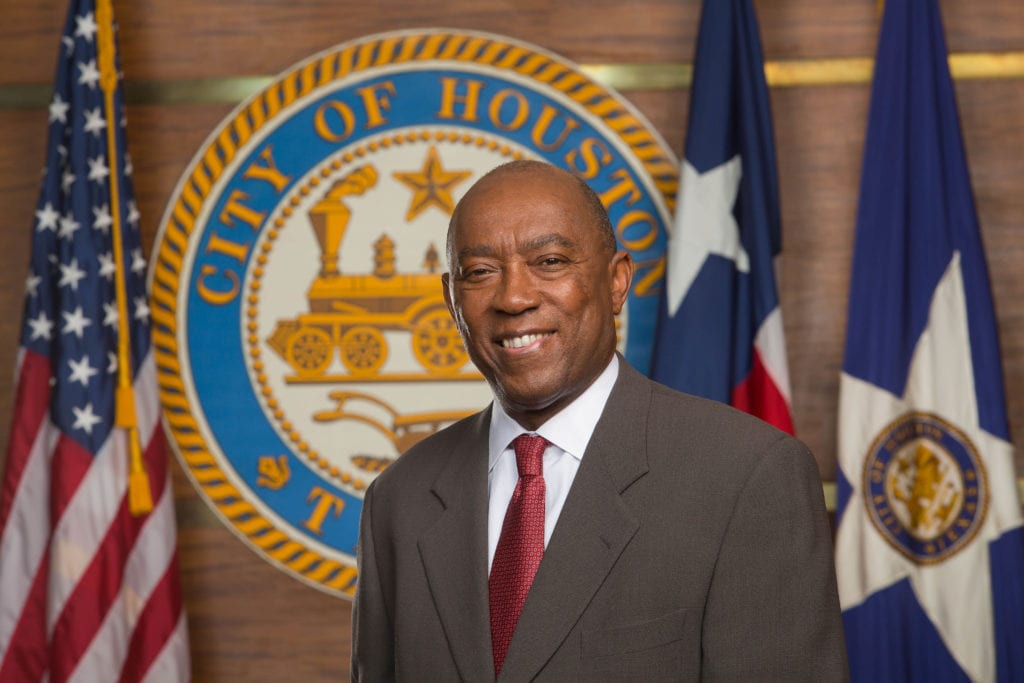

Lynn Wyatt, founding chair of the MFAH film committee, had pursued Sylvester Turner for quite some time to be part of the annual series. She made this much known as she introduced him to those seated in the museum’s Brown Auditorium Theater. Turner had made a bet with Wyatt that he would introduce a film after the election. More than a year after taking office, Mayor Sylvester Turner took to the stage to share his love for A Raisin in the Sun.

Mayor Turner was amused by the fact that Wyatt knew Sidney Poitier – she had conversed with the esteemed thespian about Turner’s upcoming introduction to one of his celebrated films. After a little revelry, the Houston mayor spoke candidly about the 1961 drama, based on Lorraine Hansberry’s Broadway play. In many respects the story parallels his upbringing. The sixth of nine children, Turner was raised in the Acres Home community in northwest Houston. When he was thirteen his father passed, and then came integration with his arrival to Klein High School. Through determination and perseverance, and a strong-willed mother, Turner would become student body president and graduate valedictorian. But he didn’t stop there; his education would take him from Houston to Harvard. His degree in Political Science, plus following law degree, only helped to strengthen the framework of the leader that Sylvester Turner would become.

Writing as someone who appreciates many forms of art, particularly film, it was a pleasure witnessing Mayor Turner share his love of cinema with A Raisin in the Sun. This is a film I may have seen during high school but twenty years and thousands of movies later I could be wrong. Sitting in a darkened theater at near capacity, watching a 35mm print of a film more than fifty years old was quite a sight. A few seats down from me sat Regina Scruggs, a fellow Houston Film Critics Society member and former host of KUHF 88.7 FM’s “Music from the Movies.” She gave me a few music trivia tidbits after the presentation including one related to James Dean and his piano teacher, Leonard Rosenman.

A Raisin in the Sun, which gets its title from the Langston Hughes poem “Harlem,” is the story of a black family’s experiences in a poor Chicago neighborhood as they try to better themselves. More than a decade before the Jeffersons moved on up from Queens to an apartment in Manhattan, the Younger family – Walter Lee (Poitier), his wife Ruth (Ruby Dee), younger sister Beneatha (Diana Sands), son Travis and mother Lena (Claudia McNeil) – lived cramped together in a small, two-bedroom apartment in Chicago’s East side.

With the passing of Lena’s husband, the family has been anticipating a life insurance check in the amount of ten thousand dollars. Walter Lee has his own ideas of what to do with the money. Invest in a liquor store so he can quit opening and closing doors for uppity white folks as their chauffer, and begin to put an end to their financial woes. Lena wants to fulfill a dream she had with her deceased husband and buy a house. Beneatha would like to use the money for tuition towards medical school.

The film has modest staging – it is based on a play, after all – and Donald Petrie’s direction is simple. What draws your attention are the performers and the performances. Sidney Poitier as Walter Lee is dynamite in his portrayal of an urban Sisyphus. The struggle he endures only to see his hopes for wealth and salvation keep crashing down. Ruby Dee is Walter’s dutiful wife, who does back-breaking housekeeping work to help make ends meet. While diminutive in stature, Dee has a come-what-may view on life as someone who may wish for more but is content by what she has – a husband, a child and a roof over her head.

What happens to a dream deferred? Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun? – Langston Hughes (1951)

Diana Sands as Beneatha, her outlook on life is defined by two gentlemen suitors. One who has fully assimilated with his smarts and style of dress (George Murichson – Louis Gossett Jr. in his debut film), while the other (Joseph Asagai) embraces his African culture. This creates an interesting contrast for Walter, his pursuit of happiness, and his ability to obtain it while still maintaining his sense of pride and heritage.

Each character undergoes some change but the matriarch of the family, played Claudia McNeil, is the most strong-minded. She is strength. She is life-affirming. She is hope for all of those around her. When they talk about glue that holds a family together, they are talking about mothers like Lena. I’m sure Mayor Turner’s mother was just as strong.

A credit must be given to writer Lorraine Hansberry and not shying away from taboo subject matter as her play was unafraid to touch on issues like abortion or segregated impediments relating to the Younger family’s move to a new neighborhood. (The all-white homeowners were fearful what might happen to their quaint suburb as a result.) In fact the only white actor in the film, John Fielder (best known as the voice of Piglet from Winnie-the-Pooh), offers the Youngers money to stay away and not move. He also uses phrases like “you people,” which sounds grating now but was normal back then.

Unlike Denzel Washington’s 2016 release Fences, also based on a play (written by August Wilson), A Raisin in the Sun has weightier importance. Maybe it’s because of the time of the film’s arrival in theaters (May, 1961). While social inequality is still persistent in today’s society, Sun arrived as the Civil Rights movement was ongoing and moving towards a tipping point. Plus, for a major studio (Columbia Pictures) to open a film starring a predominantly black cast was a heavy risk to say the least.

Sixteen years after its release, 1967 (a landmark year in cinema), Sidney Poitier would star in three films. One of them was the commercial hit To Sir, with Love. The other two would be nominated for Best Picture, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? and In the Heat of the Night. (The latter would ultimately win and be awarded the Oscar at a ceremony that was postponed for two days after the assassination of Martin Luther King. Just another reminder of how relevant the film was at the time of its release.)

In The Essentials: 52 Must-See Movies and Why They Matter written by Jeremy Arnold and the late Robert Osborne, filmmaker Rob Reiner remarked, “[Poitier] was like the Jackie Robinson of the movies. He was the first black leading man with genuine star power, the first African American whose name on the marquee brought people to the theater.”

Thank you, Mayor Sylvester Turner, for selecting A Raisin in the Sun. It remains a socially conscientious film whose messages of optimism and determination serve as reminders that even as the future seems unclear, there’s nothing that we can’t accomplish together.